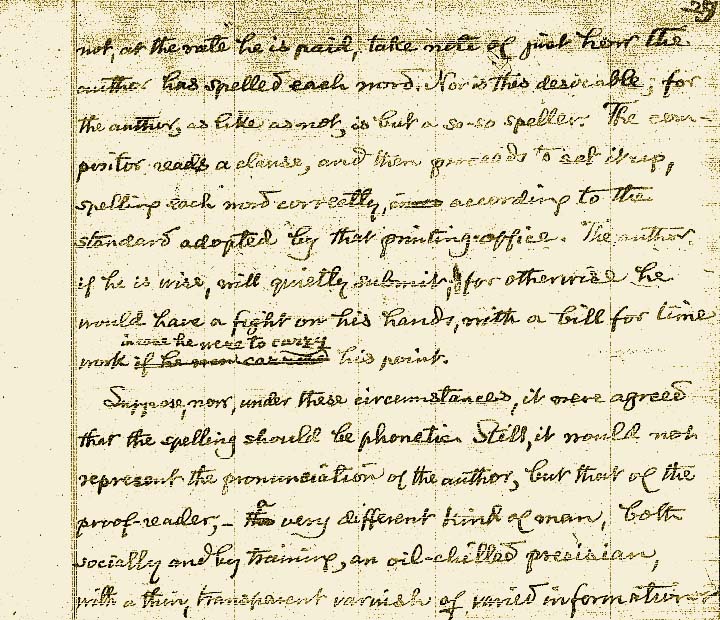

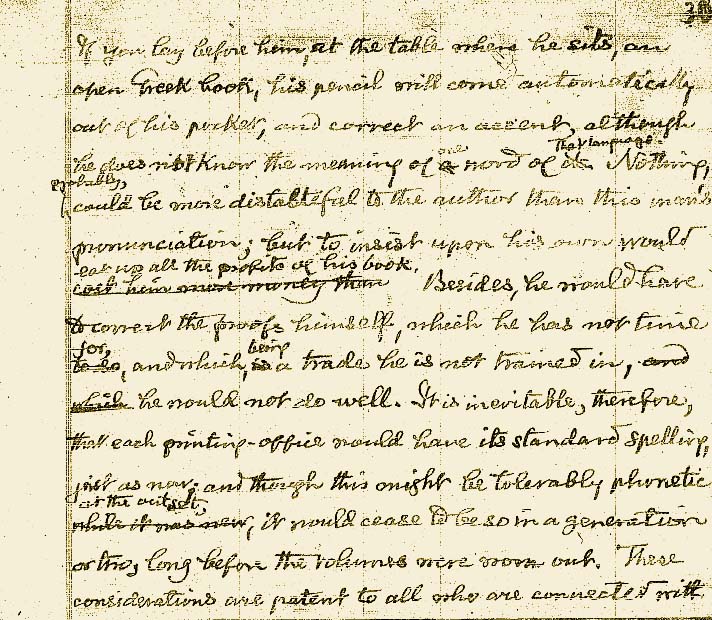

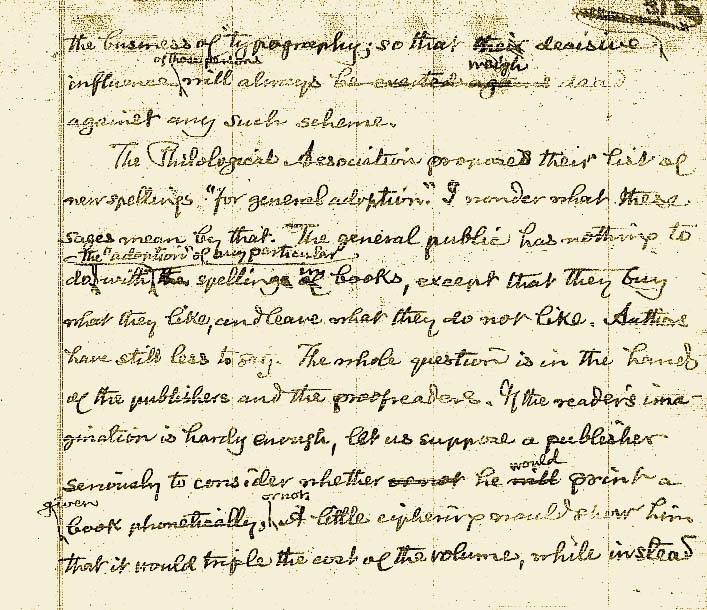

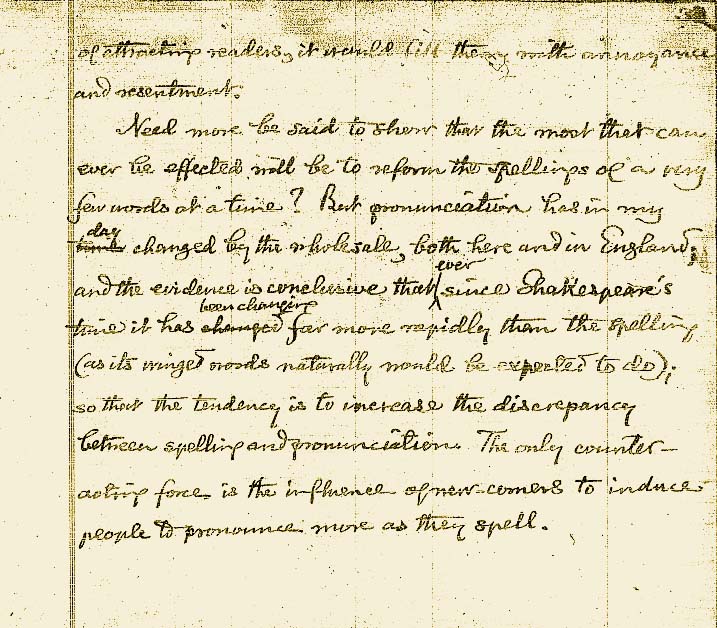

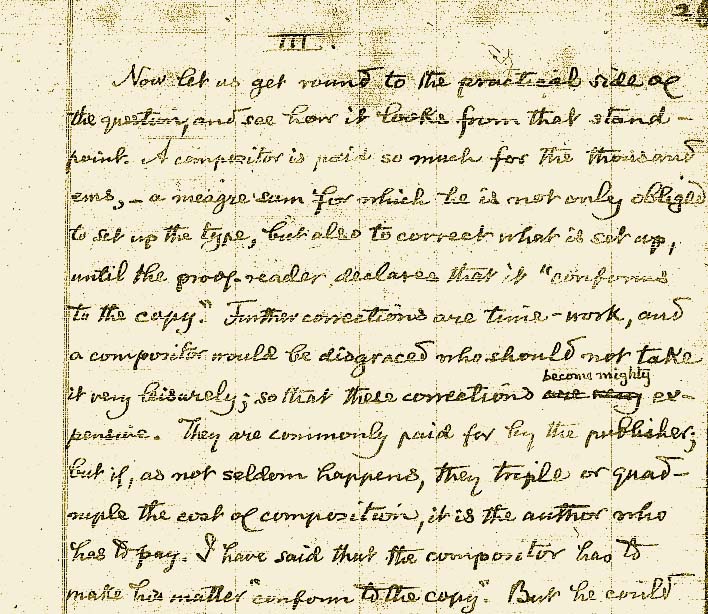

Now let us get round to the practical side of the question, and see how it looks from that stand-point. A compositor is paid so much for the thousand ems, -a meagre sum for which he is not only obliged to set up the type, but also to correct what is set up, until the proof-reader declares that it "conforms to the copy". Further corrections are time-work, and a compositor would be disgraced who should not take it very leisurely; so that these corrections become mighty expensive. They are commonly paid far by the publisher; but if, as not seldom happens, they triple or quadruple the cost of composition, it is the author who has to pay. I have said that the compositor has to make his matter "conform to the copy". But he could not,