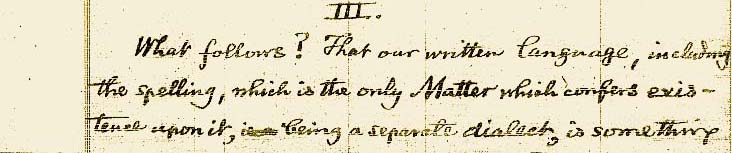

What follows? That our written language, including the spelling, which is the only Matter which confers existence upon it, being a separate dialect, is something

| Spanish translation and annotations |

|

What follows? That our written language, including the spelling, which is the only Matter which confers existence upon it, being a separate dialect, is something |

|

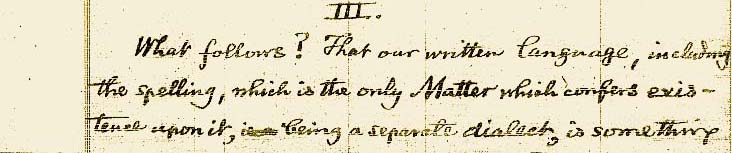

for the linguist to study, and in studying, to love, as every genuine scientific man loves the nature which is the aliment of his science.

The linguist will say that it is precisely because our spelling is not a product of nature that he hates it, -because, instead of being an involuntary outgrowth of the subconscious man, it is largely the invention of a parcel of pretentious ignoramuses. And it must be acknowledged that this sentiment, if reduced from the exaggerated proportions of a roc, as it appears through the linguist's lens, to its natural size of a wren, is normal enough. Only it belongs exclusively in the domain of good taste, which the modern linguist affects to ignore. A stern scientific man, like him, should learn to conquer such revulsions. The fact that spelling is

|

|

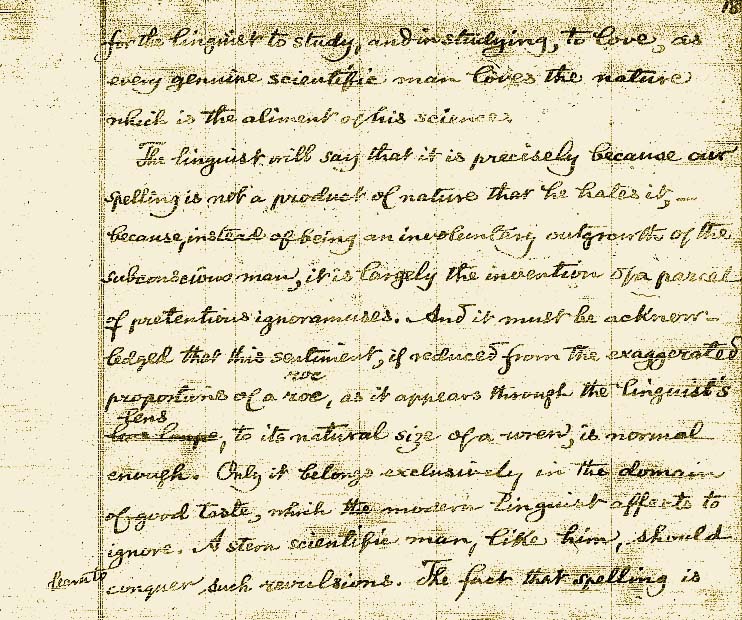

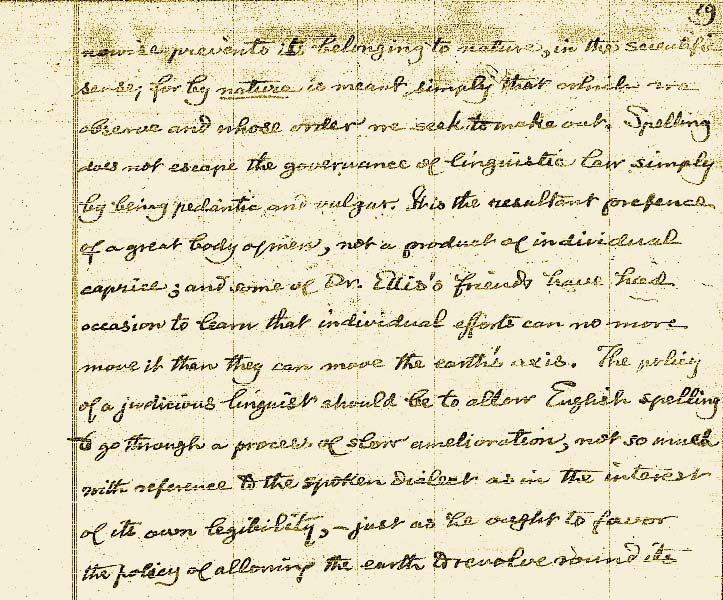

nowise prevents its belonging to nature, in the scientific sense; for by nature is meant simply that which we observe and whose order we seek to make out. Spelling does not escape the governance of linguistic law simply by being pedantic and vulgar. It is the resultant [il. ?] of a great body of men, not a product of individual caprice; and some of Dr. Ellis's friend have had occasion to learn that individual efforts can no more move it that they can move the earth's axis. The policy of a judicious linguist should be to allow English spelling to go through a process of slow amelioration, not so much with reference to the spoken dialect as in the interest of its own legibility, -just as he ought to favor the policy of allowing the earth to revolve round its |

|

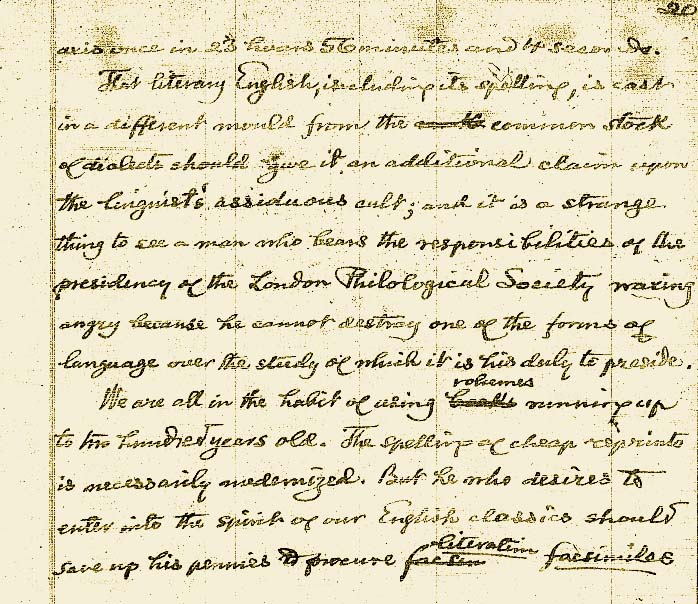

axis once in 23 hours 56 minutes and 4 seconds.

That literary English, including its spelling, is cast in a different mould from the common stock of dialects should give it an additional claim upon the linguist's assiduous cult; and it is a strange thing to see a man who bears the responsibilities of the presidency of the London Philological Society waxing angry because he cannot destroy one of the forms of language over the study of which it is his duty to preside. We are all in the habit of using volumes running up to two hundred years old. The spelling of cheap reprints is necessarily modernized. But he who desires to enter into the speech of our English classics should save up his pennies to procure literatim facsimiles

|

|

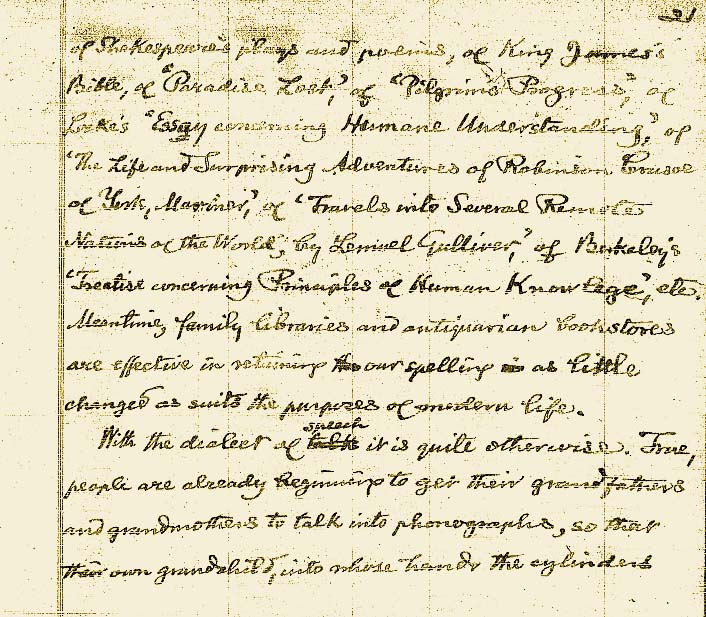

of Shakespeare's plays and poems, of King James's Bible, of "Paradise Lost", of "Pilgrim's Progress", of Locke's "Essay concerning Humane Understanding", of "The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner", of "Travels into Several Remotes Nations of the World", by "Lemuel Gulliver", of Berkeley´s "Treatise concerning Principles of Human Knowledge", etc. Meantime, family libraries and antiquarian bookstores are effective in retaining our spelling as little changed as suits the purposes of modern life.

With the dialect of speech it is quite otherwise. True, people are already beginning to get their grandfathers and grandmothers to talk into phonographs, so that their own grandchild, into whose hand the cylinders |

|

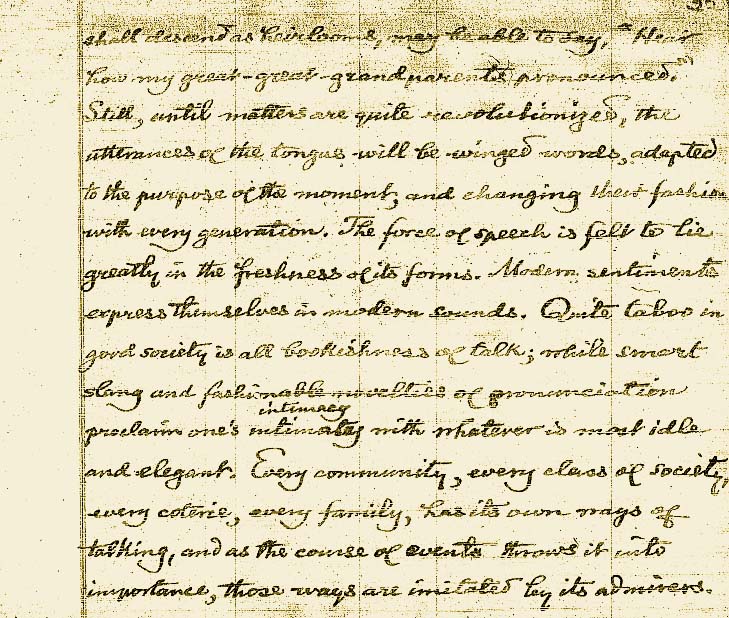

shall descend as heirlooms, may be able to say, "Hear how my great-great-grand parents pronounced". Still, until matters are quite revolutionized, the utterances of the tongue will be winged words, adapted to the purpose of the moment, and changing their fashion with every generation. The force of speech is felt to lie greatly in the freshness of its forms. Modern sentiments express themselves in modern sounds. Quite taboo in good society is all bookishness of talk; while smart slang and fashionable novelties of pronunciation proclaim one's intimacy with whatever is most idle and elegant. Every community, every class of society, every coterie, every family, has its own ways of talking, and as the course of events throws it into importance, those ways are imitated by its admirers.

|

|

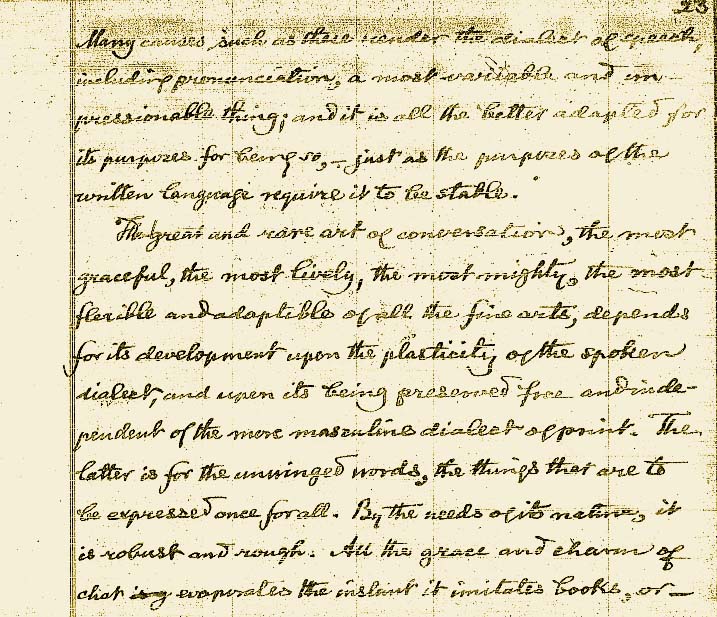

Many causes such as these render the dialect of speech, including pronunciation, a most variable and impressionable thing; and it is all the better adapted for its purposes for being so, -just as the purposes of the written language require it to be stable. The great and rare art of conversation, the most graceful, the most lively, the most mighty, the most flexible and adaptable of all the fine arts, depends for its development upon the plasticity of the spoken dialect, and upon its being preserved free and independent of the more masculine dialects of print. The latter is for the unwinged words, the things that are to be expressed once for all. By the needs of its nature, it is robust and rough. All the grace and charm of chat evaporates the instant it irritates books, or- |

|

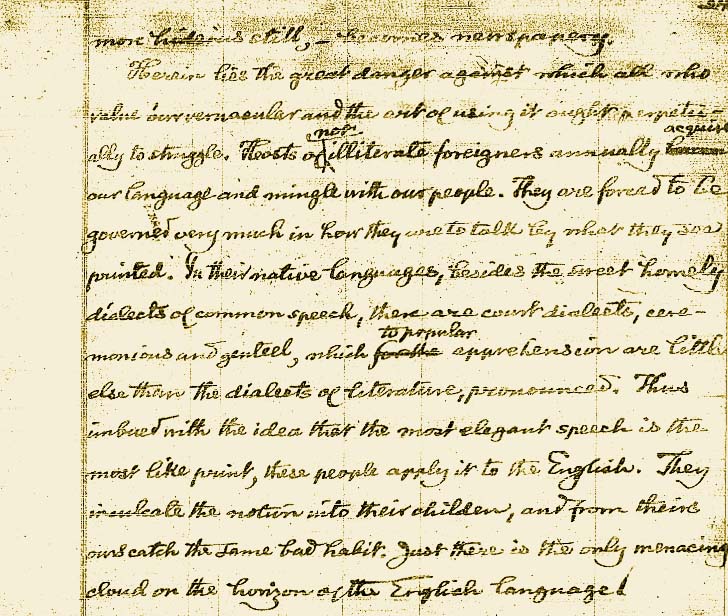

more hideous still, -becomes newspapery.

Herein lies the great danger against which all who value our vernacular and the art of using it ought perpetually to struggle. Hosts of not illiterate foreigners annually acquire our language and mingle with our people. They are forced to be governed very much in how they are to talk by what they see printed. In their native languages, besides the sweet homely dialects of common speech, there are court dialects, ceremonious and genteel, which to popular apprehension are little else than the dialects of literature, pronounced. Thus imbued with the idea that the most elegant speech is the most like print, these people apply it to the English. They inculcate the notion into their children, and from theirs ours catch the same bad habit. Just there is the only menacing cloud on the horizon of the English language. |

|

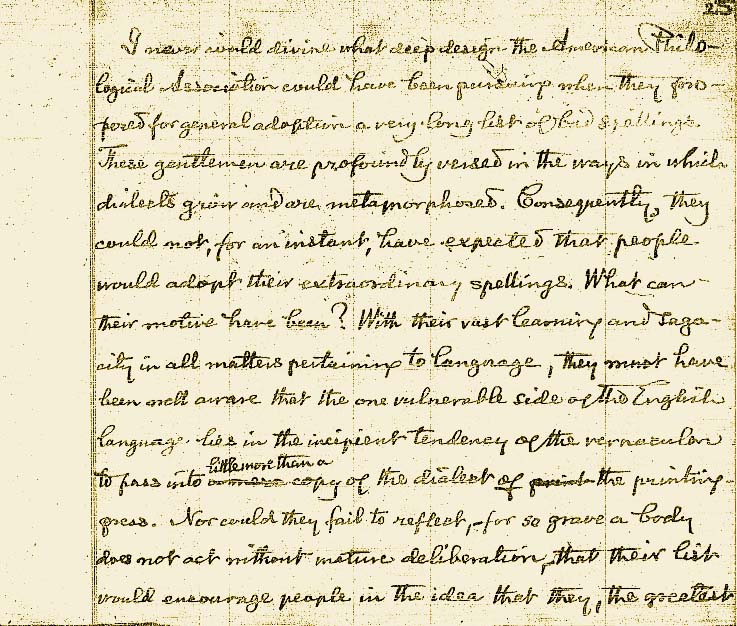

I never would divine what deep design the American Philological Association could have been pursuing when they proposed for general adoption a very long list of bad spellings. These gentlemen are profoundly versed in the ways in which dialects grow and are metamorphosed. Consequently, they could not, for an instant, have expected that people would adopt their extraordinary spellings. What can their motive have been? With their vast learning and sagacity in all matters pertaining to language, they must have been well aware that the one vulnerable side of the English language lies in the incipient tendency of the vernacular to pass into little more than a copy of the dialect of the printing-press. Nor could they fail to reflect, -for so grave a body does not act without mature deliberation, that their list would encourage people in the idea that they, the greatest |

|

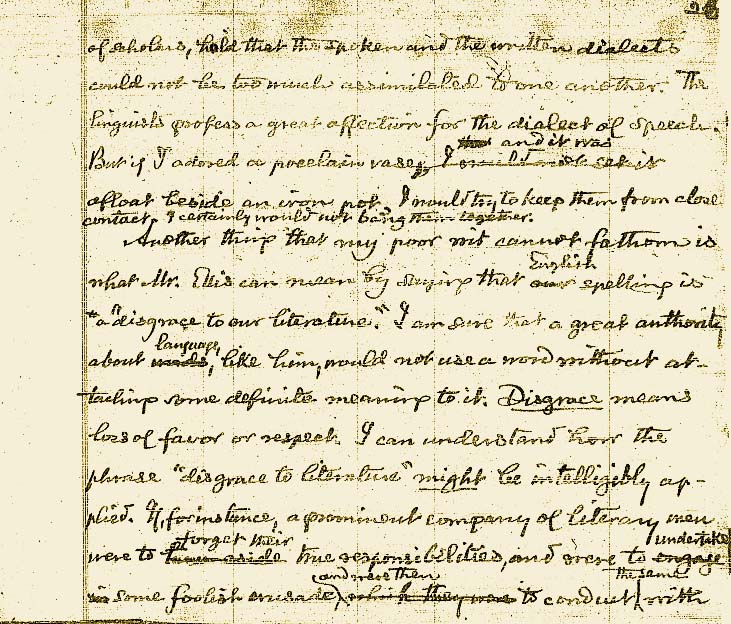

of scholars, hold that the spoken and the written dialects could not be too much assimilated to one another. The linguists profess a great affection for the dialect of speech. But if I adored a pocelain vase and it was afloat beside an iron pot, I would try to keep them from close contact. I certainly would not bang them together.

Another thing that my poor wit cannot fathom is what Mr. Ellis can mean by saying that English spelling is a "disgrace to our literature". I am sure that a great authority about language, like him, would not use a word without attaching some definite meaning to it. Disgrace means loss of favor or respect. I can understand how the phrase "disgrace to literature" might be intelligibly applied. If, for instance, a prominent company of literary men were to forget their true responsibilities, and were to undertake some foolish crusade and were then to conduct the same with |

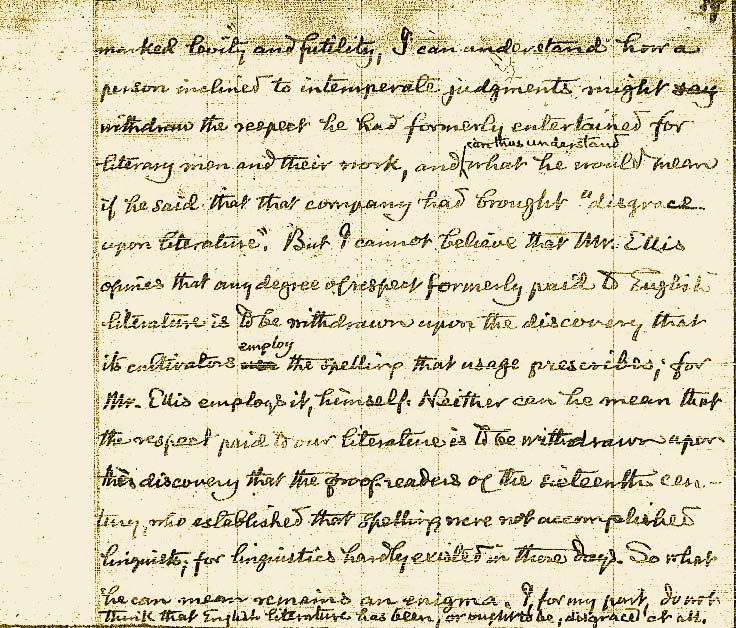

|

marked levity and futility, I can understand how a person inclined to intemperate judgments might withdraw the respect he had formerly entertained for literary men and their work, and can thus understand what he would mean if he said that that company had brought "disgrace upon literature". But I cannot believe that Mr. Ellis opines that any degree of respect formerly paid to English literature is to be withdrawn upon the discovery that its cultivators employ the spelling that usage prescribes; for Mr. Ellis employs it, himself. Neither can he mean that the respect paid to our literature is to be withdrawn upon the discovery that the proof readers of the sixteenth century, who established that spelling were not accomplished linguists; for linguistics hardly existed in those days. So what he can mean remains an enigma. I for my part, do not think that English literature has been, or ought to be, disgrace at all.

|

Transcription by Rocío Rodríguez-Tapia (2013)

Una de las ventajas de los textos en formato electrónico respecto de los textos impresos es que pueden corregirse con gran facilidad mediante la colaboración activa de los lectores que adviertan erratas, errores o simplemente mejores transcripciones. En este sentido agradeceríamos que se enviaran todas las sugerencias y correcciones a rrtapia@alumni.unav.es

Fecha del documento:12 de junio 2014

Última actualización: 12 de junio 2014