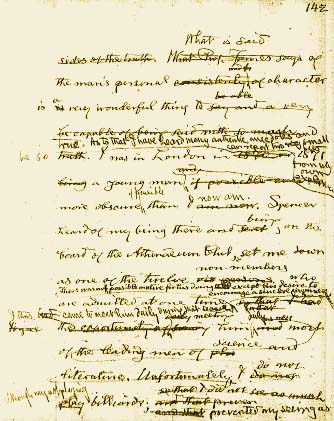

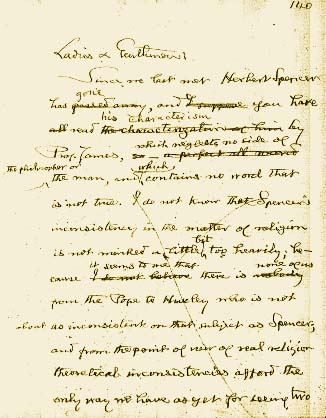

Ladies & Gentlemen,

Since we last met Herbert Spencer has gone, and you have read his characterism by Prof. James, which neglects no side of the philosopher or the man, and which contains no word that is not true.

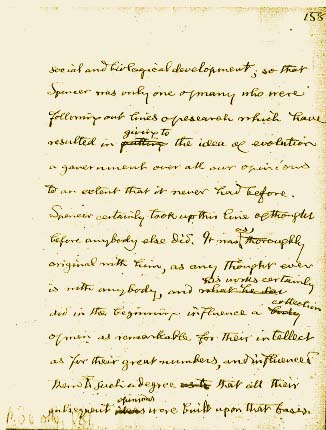

[deleted] I do not know that Spencer's inconsistency in the matter of religion is not marked a little bit too heavily; because it seems to me that is none of us from the Pope to Huxley who is not about as inconsistent on that subject as Spencer; and from the point of view of real religion theoretical inconsistencies afford the only way we have as yet for seeing two